Parasites Taking a Toll on Unsuspecting Veterans

Posted:

May 11, 2018

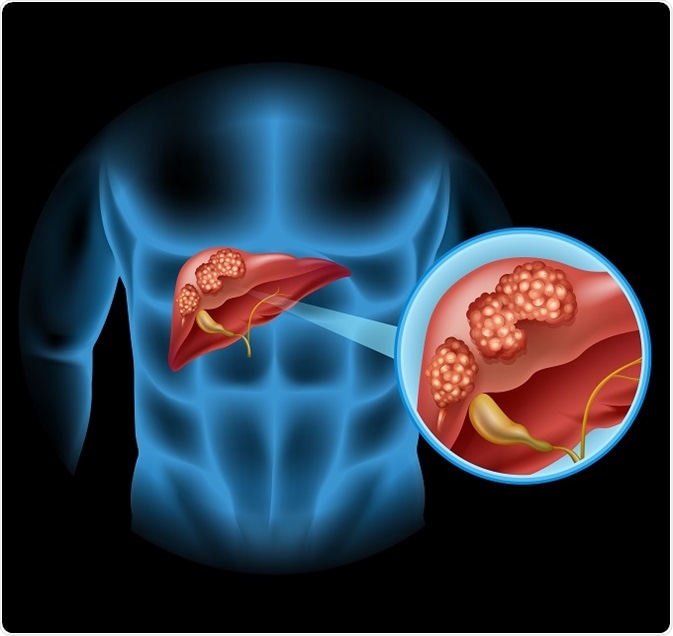

Recently, cases of cholangiocarcinoma (bile duct cancer) and hepatic pain in the United States have been described among Vietnam War veterans. The cause is Clonorchis sinensis, one of the most prevalent parasites in the world which is still transmitted in many regions of Asia. It is also known as the liver fluke worm. The fluke worm, Opisthorchis viverrini is another potential source of infection and has the same lifecycle as C. sinensis with habitat overlap, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Cases of liver fluke are rare in the United States as the parasite is not endemic to North America. In 2017, the Department of Veterans Affairs commissioned a study to investigate prevalence of liver fluke antibodies in 50 blood samples from Vietnam War veterans collected at a New York facility. Out of the 50 samples tested, more than 20% were positive. This study was issued after about 700 veterans with cholangiocarcinoma cases were observed by the Department of Veterans Affairs over the past 15 years.

Many claims for service-related benefits were not submitted, or if submitted, were rejected because the possible connection to Vietnam was unknown at the time. In 2016, 41 claims were submitted, and 60 claims were submitted in 2017. Although this type of cancer is rare, it is important for veterans and physicians to know the symptoms and tests available to diagnose this parasitic infection.

The parasite’s life cycle begins when eggs are excreted by a human host into the environment. The eggs contain larvae that hatch and begin to thrive once ingested by a snail, the first intermediate host. Inside the snail, the larvae morph into a sporocyst that will eventually lead to a second larval stage. The parasite reproduces asexually, allowing for exponential multiplication of sporocysts within the snail. These larvae exit the snail body and enter freshwater where they attach to a fish. Upon attachment, they bore into fish muscle tissue and form cysts. Many species of fish and shrimp have been recorded as potential secondary intermediate hosts. The definitive, or final host, is a human. The parasite can survive in the muscle of freshwater fish and infects the human host when the fish is consumed, either raw or undercooked. While eating raw and undercooked fish was not any of the veterans’ first choice for sustenance, but when rations ran out the soldiers often had to resort to eating whatever was available, including raw fish.

The end of the larval stage occurs when the coating of the cyst is broken down by stomach acid and the larvae enter the bile duct to feed on bile. After about a month of feeding, the larvae mature to adult trematodes and begin to lay eggs.

Up to 4,000 eggs can be produced in a day; the high density of eggs and the prevalence of fish in the diets of people living in these areas are part of what makes the parasite endemic. Over time, the liver and bile duct tissues can become inflamed or obstructed, and liver cancer or cell death can occur.

Up to 4,000 eggs can be produced in a day; the high density of eggs and the prevalence of fish in the diets of people living in these areas are part of what makes the parasite endemic. Over time, the liver and bile duct tissues can become inflamed or obstructed, and liver cancer or cell death can occur.C. sinensis induces an inflammatory reaction and can cause bile duct obstruction by the parasite itself or from its eggs. The liver fluke can be easily treated with praziquantel or albendazole if diagnosed early. While most infected persons do not show any symptoms, infections that last a long time can result in severe symptoms and serious illness. Untreated, infections may persist for up to 25-30 years, the lifespan of the parasite.

Over time, this parasite can cause life-threatening illness as it destroys the liver and can cause liver-related cancer. This pilot study indicates that liver fluke infection is fairly prevalent among Vietnam War era veterans and they should be encouraged them to get confirmatory ultrasounds to detect any abnormalities of the liver or other organs affected by this deadly parasite.

by Anna Klavins

R&D Microbiologist

HARDY DIAGNOSTICS

0 Comment(s)