Howard Florey: The Man Who Was First to Make Penicillin

Saving lives during WWII

Howard Walter Florey was a famed pathologist and pharmacologist from Australia known for being one of the first researchers to manufacture penicillin. Before his success with penicillin, Florey was on the hunt for a naturally occurring antibacterial substance. While studying tissue inflammation and secretions of the mucous membrane, Florey successfully purified lysozyme. After reading Alexander Fleming’s paper on the Penicillium mold and how it inhibited bacteria, Florey, along with several colleagues, revived the research and were able to produce their own drug. At this time, gallons of broth were required to manufacture enough penicillin to cover a fingernail.(5) Florey would later share the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Alexander Fleming and Ernst Chain for their development of penicillin. It’s estimated that the actions of the Nobel Prize laureates’ saved upwards of 200 million lives.(1)

As an early test, Florey and his colleagues injected eight mice with a virulent strain of Streptococcus. Four of the infected mice were injected with penicillin while the other four were used as a control with no treatment. The next morning, all of the mice treated with penicillin were alive, while the control mice had died.(6) This gave Florey the confidence to test the drug on humans, starting with a young patient suffering from terminal cancer. While the initial results were disheartening, it was determined that an adverse reaction of fever and trembling was caused by impurities within the drug, and not by the drug itself.

After penicillin had passed the initial phases of development, Florey moved on to curing the first patient. Police constable Albert Alexander was injured during World War II and was suffering from an infection of both Staphylococcus and Streptococcus.(3,4) Alexander was given an initial infusion of penicillin and within 24 hours his fever had been reduced, his appetite was restored, and his infection began to heal. Alexander’s reaction was promising, but his recovery was limited by penicillin production. After the fifth day, despite recycling the penicillin from Alexander’s urine, the drug had run out. Due to war-time restrictions on Florey’s laboratory, scientists were unable to produce more and Alexander relapsed and died.(1) Florey would later focus on treating children due to the lower volume of drug required to treat smaller bodies.

During World War II, penicillin production became of the utmost importance due to the high death rate of soldiers from infection. At one point, the British-American effort to mass-produce penicillin involved thousands of people from university departments, government agencies, pharmaceutical companies, and research foundations. In response to the finicky nature of Penicillium, Pfizer executive, John Smith, said, “The mold is as temperamental as an opera singer, the yields are low, the isolation murder, the purification invites disaster.”(1) The drug was so scarce that the urine from patients who had been injected was recovered, the penicillin extracted, and then re-injected to other soldiers in need. Thanks to the focused efforts to produce larger quantities of penicillin and the lifting of wartime restrictions, the drug was available to the American public by 1945. Nearly 80 years later, penicillin is still used for ailments such as throat infections and meningitis, though the drug has seen significant reduction in applications due to the ongoing development of antibiotic resistance. Despite this, no life remains untouched by Florey, Alexander, and Chain’s invaluable contributions to microbiology and humanity in general.

By Alexandra Lopez

HARDY DIAGNOSTICS

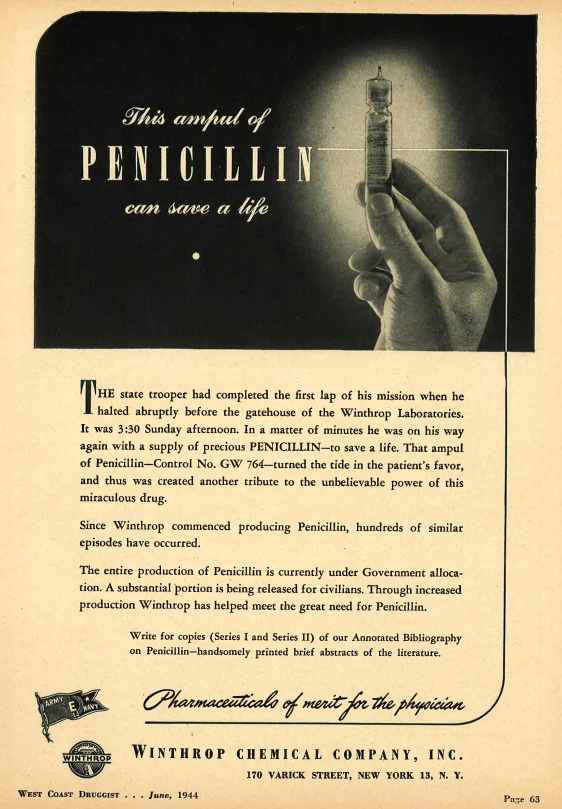

The photo below is from a pharmacist magazine published in June of 1944, about one year before the war ended in Europe. Penicillin was being rationed by the government with most of the precious doses going to soldiers overseas.