Alexander Fleming: A Pioneer for Antimicrobial Stewardship

On August 6th, 1881, Sir Alexander Fleming was born in Ayrshire, Scotland to Hugh Fleming and Grace Stirling Morton. After gaining an education at various schools in Scotland and London, he graduated with a Bachelor of Medicine and a Bachelor of Surgery from St. Mary's Hospital Medical School at London University, receiving a gold metal as the top medical student in 1908. Fleming served as a private in the London Scottish Regiment of the Territorial Army Volunteer Force from 1900 to 1914, where he became quite a recognized marksman. This marksmanship was admired by the captain of the St. Mary's rifle club who desperately wanted to recruit Fleming in order to improve his teams’ standings. Therefore, the captain convinced Fleming to not only join the club, but to pursue a career in research rather than surgery, since the latter would require him to transfer to another school. Unbeknownst to anyone, this is when Fleming's career as an esteemed bacteriologist would begin.

When World War I broke out, Fleming had moved up ranks to a captain in the Army Medical Corps where he worked in battlefield hospitals at the Western Front in France. There, he witnessed the death of many soldiers from sepsis resulting from infected wounds. Antiseptics were used to treat wounds, and Fleming began to observe that this treatment often worsened the injuries. In a 1917 article published in the medical journal, The Lancet, he described an experiment he conducted in which he explained why antiseptics were killing more soldiers than the infection itself. Antiseptics worked well on the surface, but deep wounds tended to shelter anaerobic bacteria from the antispectic agent. Antiseptics seemed to also cause damage to the cells and tissue around the wound in addition to killing the bacteria. These superficial antiseptics also did nothing to remove the anaerobic bacteria deeper into the wound.[1] No one seemed to pay much attention at the time to Fleming’s observation of the presence of anaerobic bacteria in deep wounds.

After the war, back at St. Mary’s Hospital, Fleming was experimenting with bacteria on agar plates when he found that one of the plates was contaminated with bacteria from the air.

When he added nasal mucus, he found that the mucus inhibited the bacterial growth.[2] Surrounding the mucus area was a clear, transparent circle, indicating what we now refer to as the zone of inhibition. He continued these tests with sputum, cartilage, blood, semen, ovarian cyst fluid, pus, and egg white, which showed that the antimicrobial agent was present in all.[3] In the 1922 issue of the Proceedings of the Royal Society D: Biological Sciences, Fleming wrote, “In this communication I wish to draw attention to a substance present in the tissues and secretions of the body, which is capable of rapidly dissolving certain bacteria. As this substance has properties akin to those of ferments I have called it a Lysozyme.” This was the first recorded discovery of lysozyme.

In his Nobel lecture in 1945, he mentioned lysozyme, “Penicillin was not the first antibiotic I happened to discover.” [4]

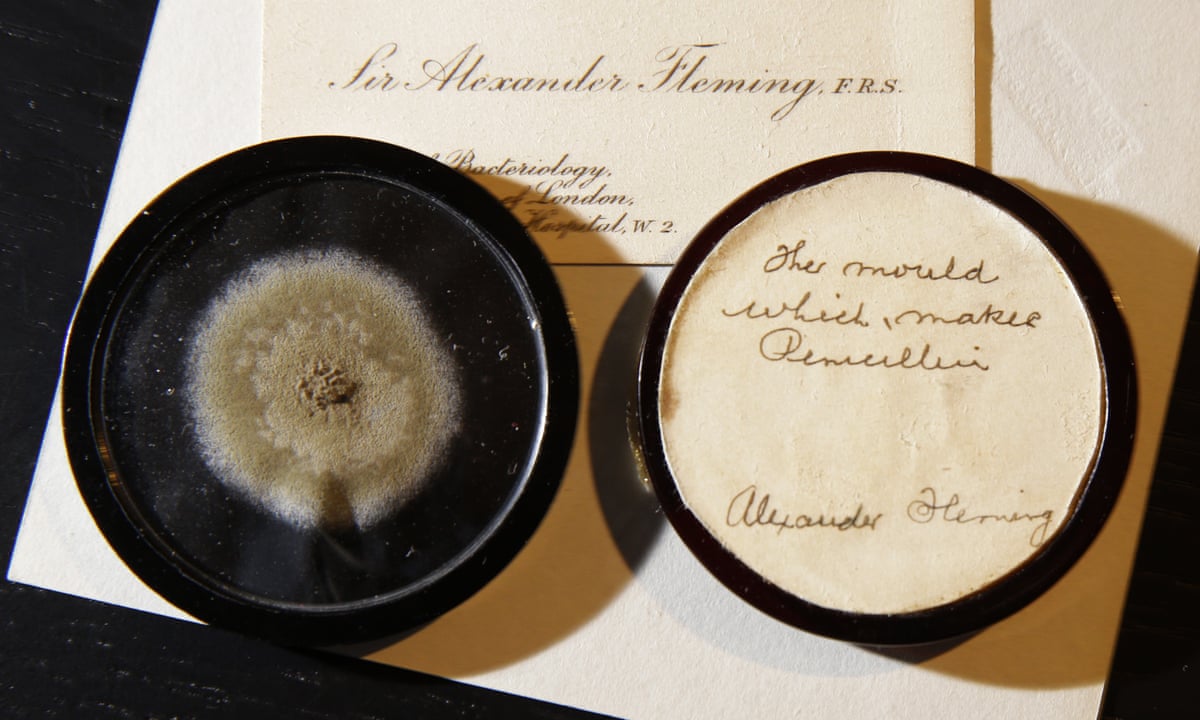

In 1928, Fleming was working with Staphylococcus aureus, when he left an inoculated culture plate on a bench in the corner of his laboratory. The rest, as we say, is history. His accidental discovery led to the identification of what he named penicillin and revolutionized decades of antibiotic treatment. His discovery of penicillin has been described as the, “single greatest victory ever achieved over disease.”

Noted in the Marvels of Science, Fleming is quoted as saying, “One sometimes finds what one is not looking for. When I woke up just after dawn on September 28, 1928, I certainly didn't plan to revolutionize all medicine by discovering the world's first antibiotic, or bacteria killer. But I suppose that was exactly what I did.” [5]

Fleming received many awards for his achievements and obtained somewhere around thirty honorary degrees. In 1944, he was made a Knight Bachelor by King George VI and a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Alfonso X the Wise in 1948. In 1999, he was named in Time magazine’s list of the 100 Most Important People of the 20th century.

Sources:

1 Fleming, Alexander (September 1917). "The Physiological and Antiseptic Action of Flavine (With Some Observations on the Testing of Antiseptics)". The Lancet. 190 (4905): 341–345. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)52126-1

2 Fleming, A. (1922). "On a remarkable bacteriolytic element found in tissues and secretions". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 93 (653): 306–317. Bibcode:1922RSPSB..93..306F. doi:10.1098/rspb.1922.0023

3 Lalchhandama, Kholhring (2020). "Reappraising Fleming's snot and mould". Science Vision. 20 (1): 29–42. doi:10.33493/scivis.20.01.03

4 Fleming, A. (1945). "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1945 -Penicillin: Nobel Lecture". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

5 Haven, Kendall F. (1994). Marvels of Science : 50 Fascinating 5-Minute Reads. Littleton, Colo: Libraries Unlimited. p. 182. ISBN 1-56308-159-8.

Free Resources

Meet the author

CLINICAL PRODUCT MANAGER at HARDY DIAGNOSTICS

Megan Roesner, B.A. Journalism and Mass Communications

Megan is a seasoned writer and marketing professional who comes from a background in television journalism, followed by fifteen years leading mulitple hospital marketing and communications teams with the largest not-for-proft health system in the U.S. Megan has won numerous tv, writing and marketing awards and is a member of a number of professional public relations and marketing associations. Her passion for continuous professional challenges and life-long learning led her to Hardy Diagnostics. Megan is proud to work amongst a wonderful marketing team surrounded by experienced microbiologists and scientists who constantly push for the latest and greatest products to help diagnose and detect disease. In her current role, Megan is in charge of product development and marketing Hardy's clinical category which encompasses hospitals and health systems, clinics and research institutions, higher education and veterinary diagnostics. In her free time, Megan enjoys being a mom to her two very active boys, cats, a dog, a very old goldfish and 24 chickens.